Palm Beach County

African American Oral History Project

Sponsored By

BACKGROUND

Segregation Life in Palm Beach County

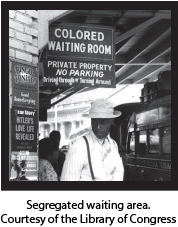

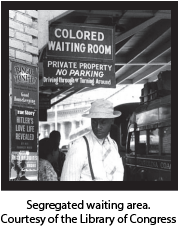

A segregated life was the norm for people of color in Palm Beach County. Segregation and discrimination existed in the school system, businesses, housing, and people of color’s everyday lives. After the Civil War, the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifteenth amendments were passed in 1865, 1866, and 1869 respectively to ensure the rights of the recently freed slaves. However, State governments were given the liberty to adopt the “separate but equal” doctrine, which meant that whites and blacks had the same rights. Still, each State had the liberty to use separate institutions to facilitate these rights.

A segregated life was the norm for people of color in Palm Beach County. Segregation and discrimination exis-ted in the school system, businesses, housing, and people of color’s everyday lives. After the Civil War, the thirteenth, fourteenth, and fifte-enth amendments were passed in 1865, 1866, and 1869 respectively to ensure the rights of the recently freed slaves. However, State governments were given the liberty to adopt the “separate but equal” doctrine, which meant that whites and blacks had the same rights. Still, each State had the liberty to use separate institutions to facilitate these rights.

From the 1880s to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws allowed and enforced racial segregation between African Americans and white Americans. These laws were created to deny blacks basic civil and socio economic rights, such as the right to vote. African Americans were mainly powerless to these laws since it legalized discrimination against them. They could not do anything to their white counterparts without being arrested, fined, or executed for their retaliation. For instance, Ms. Munnings described the preference and popularity of catalog shopping to avoid the humiliation and restrictions of blacks in the stores.

From the 1880s to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws allowed and enforced racial segregation between African Americans and white Americans. These laws were created to deny blacks basic civil and socio economic rights, such as the right to vote. African Americans were mainly powerless to these laws since it legalized discrimination against them. They could not do anything to their white counterparts without being arrested, fined, or executed for their retaliation. For instance, Ms. Munnings described the preference and popularity of catalog shopping to avoid the humiliation and restrictions of blacks in the stores.

“They would order from Montgomery Ward. They gave these big catalogs and from Sears Roebuck…that’s where we would do our shopping because it was just easier and it was less confining and less restricting to order something without going through all of the embarrassment and so forth that you would have to go through on Clematis Street” (Elizabeth Munnings, West Palm Beach)

From the 1880s to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws allowed and enforced racial segregation between African Americans and white Americans. These laws were created to deny blacks basic civil and socio economic rights, such as the right to vote. African Americans were mainly powerless to these laws since it legalized discrimination against them. They could not do anything to their white counter-parts without being arrested, fined, or executed for their retaliation. For instance, Ms. Munnings des-cribed the preference and popularity of catalog shopping to avoid the humiliation and restrictions of blacks in the stores.

From the 1880s to the 1960s, Jim Crow laws allowed and enforced racial segregation between African Americans and white Americans. These laws were created to deny blacks basic civil and socio economic rights, such as the right to vote. African Americans were mainly powerless to these laws since it legalized discrimination against them. They could not do anything to their white counter-parts without being arrested, fined, or executed for their retaliation. For instance, Ms. Munnings des-cribed the preference and popularity of catalog shopping to avoid the humiliation and restrictions of blacks in the stores.

“They would order from Montgomery Ward. They gave these big catalogs and from Sears Roebuck…that’s where we would do our shopping because it was just easier and it was less confining and less restricting to order something without going through all of the embarrassment and so forth that you would have to go through on Clematis Street” (Elizabeth Munnings, West Palm Beach)

“Aside from the obvious influence of Jim Crow laws in education, the elders described some of the laws in effect in their communities that limited their use of public spaces: Separate bathrooms: “Well, there was certain places in the store that you weren’t supposed to go, like the bathrooms. It was just different down there…In fact, the only store down there that had a real decent bathroom for black people was Montgomery Ward. It was a nice bathroom and it was always clean.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

Separate bathrooms: “Well, there was certain places in the store that you weren’t supposed to go, like the bathrooms. It was just different down there…In fact, the only store down there that had a real decent bathroom for black people was Montgomery Ward. It was a nice bathroom and it was always clean.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

Separate bathrooms: “Well, there was certain places in the store that you weren’t supposed to go, like the bathrooms. It was just different down there…In fact, the only store down there that had a real decent bathroom for black people was Montgomery Ward. It was a nice bathroom and it was always clean.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

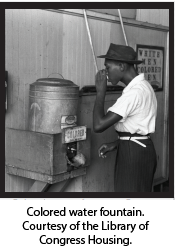

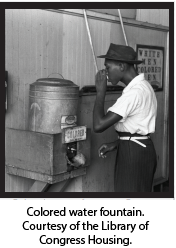

Separate water fountains: “We knew not to cross Swinton. Like I said, we were not supposed to, you know…you had your white fountains, water fountains, your colored fountains and Doc’s…We used to walk, we could walk on Sunday afternoons between church and BTU. We would walk that far and go you know go get ice cream or something. One Sunday we was like let’s taste their water let’s see what their water tastes like, and we did. It didn’t taste no different.” (Gloria Chaney, Delray Beach)

Separate bathrooms: “Well, there was certain places in the store that you weren’t supposed to go, like the bathrooms. It was just different down there…In fact, the only store down there that had a real decent bathroom for black people was Montgomery Ward. It was a nice bathroom and it was always clean.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

Separate bathrooms: “Well, there was certain places in the store that you weren’t supposed to go, like the bathrooms. It was just different down there…In fact, the only store down there that had a real decent bathroom for black people was Montgomery Ward. It was a nice bathroom and it was always clean.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

Separate water fountains: “We knew not to cross Swinton. Like I said, we were not supposed to, you know…you had your white fountains, water fountains, your colored fountains and Doc’s…We used to walk, we could walk on Sunday afternoons between church and BTU. We would walk that far and go you know go get ice cream or something. One Sunday we was like let’s taste their water let’s see what their water tastes like, and we did. It didn’t taste no different.” (Gloria Chaney, Delray Beach)

Limited use of sidewalks: “I think one of my earliest experiences with segregation and of course I didn’t understand it at that time. My father and I were going to the post office one day and we were walking and I remembered this guy, a white man met us and looked at us and he said, ‘Harvey get off the sidewalk.’ After we had passed him, I asked him, I said ‘daddy why did that man ask you to get off the sidewalk’ and he said, ‘well darling, one day I will explain it to you. You wouldn’t understand the situation’, and actually I did not understand why he was asked, to get off the sidewalk to let him by.”’ (Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

Housing

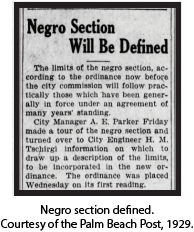

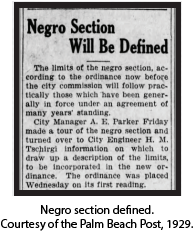

In the United States, laws required white people and people of color to live separately. Jim Crow laws extended from the 1880s to the 1960s, which allowed the legal segregation of black communities from white communities. For example, in West Palm Beach, the “Negro Segregation Ordinance” proposed by the city commission in 1929 established the “negro section” to extend from Clematis Street to Twenty third street between the railroad and Clear Lake. Several elders described how they were assigned specific areas of the cities in which they lived.

“We lived in one area and caucasians lived in the other area. West of town was the segregated part and east toward the beach was not segregated.” (Alfred Straghn, Delray Beach)

Housing

In the United States, laws required white people and people of color to live separately. Jim Crow laws extended from the 1880s to the 1960s, which allowed the legal segregation of black communities from white communities. For example, in West Palm Beach, the “Negro Segregation Ordinance” proposed by the city commission in 1929 established the “negro section” to extend from Clematis Street to Twenty third street between the railroad and Clear Lake. Several elders described how they were assigned specific areas of the cities in which they lived.

“And we lived down the hill and white people lived up the hill. That was the whole thing from Fern Street through Clematis Street. When it came to 1st Street they were able to live from Sapodilla to Rosemary but then all the rest of it was white area.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

It was not until 1968 that the Fair Housing Act was enacted under the Civil Rights Act. The Fair Housing Act penalizes discrimination based on race, color, religion, sex, or national origin in renting or buying. Neighborhoods remained segregated for several years after.

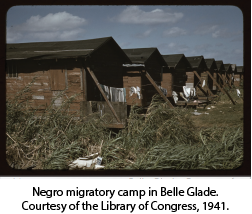

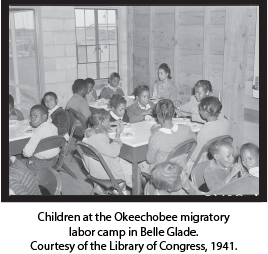

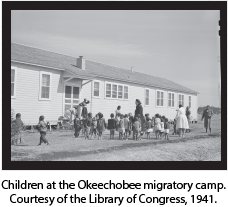

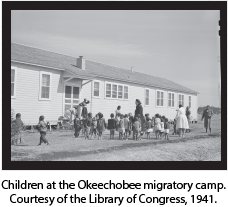

Farming

The fertility of the land surrounding Lake Okeechobee in Palm Beach County demanded a large amount of labor to harvest its crops, making this one of the only sources of work for blacks and migrant workers. Segregation for people of color living out west in Belle Glade was not much different. Although both black and white migrant workers farmed the land, they had separate living quarters. Ms. Rains said that the housing projects had rooming houses. Most of the time, these houses only had one communal bathroom for everyone to share, which was an unhealthy and unsanitary way for people to live. According to The Miami Herald in 1965, State officials were concerned about the housing conditions in Belle Glade’s “negro section.” They found crowded houses without parking spaces, no place to hang out clothes, no play areas for children, and littered streets.

The fertility of the land surrounding Lake Okeechobee in Palm Beach County demanded a large amount of labor to harvest its crops, making this one of the only sources of work for blacks and migrant workers. Segregation for people of color living out west in Belle Glade was not much different. Although both black and white migrant workers farmed the land, they had separate living quarters. Ms. Rains said that the housing projects had rooming houses. Most of the time, these houses only had one communal bathroom for everyone to share, which was an unhealthy and unsanitary way for people to live. According to The Miami Herald in 1965, State officials were concerned about the housing conditions in Belle Glade’s “negro section.” They found crowded houses without parking spaces, no place to hang out clothes, no play areas for children, and littered streets.

Ms. Biggs described a different way farming affected housing in Pahokee. Most of the land in Pahokee was designated for farming and for people of color to obtain land to build their homes, people had to come together to purchase the land. These homes were not of the same quality as the homes built for white people, which angered blacks to pay more for less quality.

“Out here where I live now, we had a group of young black men that got together and helped us be able to get homes in the city of Pahokee. They had to pursue or purchase land from the farmers or whoever that had the properties so that we could be able to build homes that we could live in. However, the homes…I call them substandard to the white houses that were built. We may have had to pay more, but the homes themselves didn’t equal up to the houses that white people lived in.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

Education

Segregations laws determined the educational outcomes and resources allocated for people of color. In 1895, it was a penal offense in Florida for black and white students to be taught in the same building or by the same teachers. The punishment was three to six months of jail time or a fine between $150 and $500. In 1927, it was against the law for white teachers to teach black students and vice versa.

Education

Segregations laws determined the educational outcomes and resour-ces allocated for people of color. In 1895, it was a penal offense in Florida for black and white students to be taught in the same building or by the same teachers. The punishment was three to six months of jail time or a fine between $150 and $500. In 1927, it was against the law for white teachers to teach black students and vice versa.

There was unequal funding for the black schools within a segregated school system compared to the white schools. According to The Palm Beach Post in 1940, the Palm Beach County School District gave the Belle Glade White School $75,000 while giving the Belle Glade Colored School $20,000. That same year, the district gave West Palm Beach Central School $108,000 versus $80,000 to the Industrial Colored School. The unequal and unfair distribution of funding given to black schools reflected in the quality of the supplies they received, specifically textbooks. Most of the elders described getting books handed down from white schools.

There was unequal funding for the black schools within a segregated school system compared to the white schools. According to The Palm Beach Post in 1940, the Palm Beach County School District gave the Belle Glade White School $75,000 while giving the Belle Glade Colored School $20,000. That same year, the district gave West Palm Beach Central School $108,000 versus $80,000 to the Industrial Colored School. The unequal and unfair distribution of funding given to black schools reflected in the quality of the supplies they received, specifically textbooks. Most of the elders described getting books handed down from white schools.

“Our books came from the white schools. They were already outdated, tattered, pages missing all of that kind of stuff.” (Gloria Chaney, Delray Beach)

There was unequal funding for the black schools within a segregated school system compared to the white schools. According to The Palm Beach Post in 1940, the Palm Beach County School District gave the Belle Glade White School $75,000 while giving the Belle Glade Colored School $20,000. That same year, the district gave West Palm Beach Central School $108,000 versus $80,000 to the Industrial Colored School. The unequal and unfair distribution of funding given to black schools reflected in the quality of the supplies they received, specifically textbooks. Most of the elders described getting books handed down from white schools.

“We did not have enough books, but we had hand-me down books there. The words were scratched out, so we called…there was another name for it, I’ll think of it later, but the books were old, and the children would write them up and scratch him up, so we was glad to have books and to know how to read.” (Lucille Fletcher, Belle Glade)

“The white students would then sign their name in the new books. When they finished with the books they would then be passed down to us, the colored Pahokee Elementary students. Sometimes pages were either torn or completely torn out; yet we managed, we learned, and we achieved. On one occasion the books were sent to us, the colored black Pahokee Elementary by mistake. Our Principal, Mr. Murrell at that time had each of us sign our names in the new books immediately. He knew that the school board would try to retrieve the books, and therefore, knowing too that they would not take them back if we had signed them. Therefore, we were able to keep the books. This angered the board and thereby we were ordered to change the name of our school. Principal Murrell had a contest to name the school, this was in the 50’s. The school was named East Lake, as I said before it was Pahokee.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

“The white students would then sign their name in the new books. When they finished with the books they would then be passed down to us, the colored Pahokee Elementary students. Sometimes pages were either torn or completely torn out; yet we managed, we learned, and we achieved. On one occasion the books were sent to us, the colored black Pahokee Elementary by mistake. Our Principal, Mr. Murrell at that time had each of us sign our names in the new books immediately. He knew that the school board would try to retrieve the books, and therefore, knowing too that they would not take them back if we had signed them. Therefore, we were able to keep the books. This angered the board and thereby we were ordered to change the name of our school. Principal Murrell had a contest to name the school, this was in the 50’s. The school was named East Lake, as I said before it was Pahokee.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

“The white students would then sign their name in the new books. When they finished with the books they would then be passed down to us, the colored Pahokee Elementary students. Sometimes pages were either torn or completely torn out; yet we managed, we learned, and we achieved. On one occasion the books were sent to us, the colored black Pahokee Elementary by mistake. Our Principal, Mr. Murrell at that time had each of us sign our names in the new books immediately. He knew that the school board would try to retrieve the books, and therefore, knowing too that they would not take them back if we had signed them. Therefore, we were able to keep the books. This angered the board and thereby we were ordered to change the name of our school. Principal Murrell had a contest to name the school, this was in the 50’s. The school was named East Lake, as I said before it was Pahokee.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

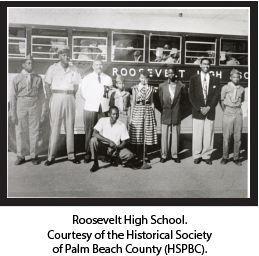

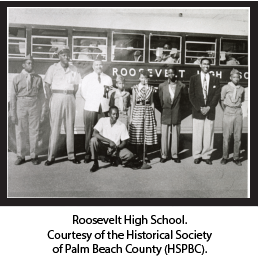

Unequal funding also affected accessibility to school. During segregation, children of color were not offered transportation, so students had to either walk or move in with friends or family that lived close to the school. Industrial High School in West Palm Beach was opened in 1914 as the only high school for students of color in Palm Beach County.

Ms. Munnings, who attended Industrial High, said that the school serviced people from all over the county. Children would come from Delray, the Glades area, and other places to complete their high school education. Ms. Lopez expressed how white students on buses would shout racial insults while walking to school at Industrial even though Palm Beach High School, a white school, was right across the street from her home.

“I lived on Fern and the white school was on the next street from me. And of course you know we could not go to that school. We weren’t allowed to go. And the school I have gone down on Gardenia many of days to get books from the book building from the white school and bring over to the black school for us to use. I have been there, I know.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

“I lived on Fern and the white school was on the next street from me. And of course you know we could not go to that school. We weren’t allowed to go. And the school I have gone down on Gardenia many of days to get books from the book building from the white school and bring over to the black school for us to use. I have been there, I know.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

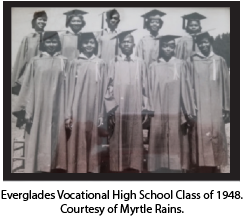

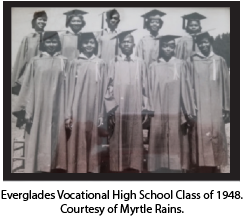

Carver High School opened in 1937 in Delray Beach for students of color in south Palm Beach County. In west Palm Beach County, students stopped attending school after 8th grade or traveled to West Palm Beach or Miami to finish high school until Everglades Vocational High school was opened in the 1940s in the city of Belle Glade.

“I lived on Fern and the white school was on the next street from me. And of course you know we could not go to that school. We weren’t allowed to go. And the school I have gone down on Gardenia many of days to get books from the book building from the white school and bring over to the black school for us to use. I have been there, I know.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

“I lived on Fern and the white school was on the next street from me. And of course you know we could not go to that school. We weren’t allowed to go. And the school I have gone down on Gardenia many of days to get books from the book building from the white school and bring over to the black school for us to use. I have been there, I know.” (Mary Lopez, West Palm Beach)

Carver High School opened in 1937 in Delray Beach for students of color in south Palm Beach County. In west Palm Beach County, students stopped attending school after 8th grade or traveled to West Palm Beach or Miami to finish high school until Everglades Vocational High school was opened in the 1940s in the city of Belle Glade.

“It was a small school, grades one through eight. At that time, and this is in the late 30s, it was the only school for blacks in the Glades area. As a matter of fact, after a kid finished the 8th grade they could not finish [high school]…In the early 40s, in the Okeechobee Center, which was a housing project, this is where we had the high school for the African American kids in the Glades area.” (Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

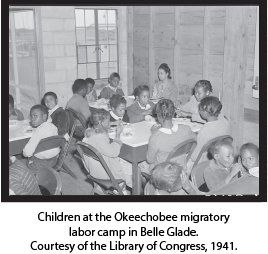

Farming in Connection to Children

The need for labor was so great that even the children of farmers were vital for working the fields. Elders from Belle Glade and Pahokee described working on the field before or after school, on the weekends, and in the Summer

“Everything in this area, the farmers and the school board worked together because the school district allowed us to be out of school during the time; it was a time for the harvesting of the crops, so that the kids could go to the fields and work but my parents never did allow us to go to the field and work except on Saturdays and on Holiday. That is something that I always look forward to doing because I always wanted to work. Even in the summertime, kids would leave school early, get on the back of trucks and travel from Belle Glade, all the way up to Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, New York, New Jersey on the back of trucks to work. I mean, this is how they lived.” ( Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

“Everything in this area, the farmers and the school board worked together because the school district allowed us to be out of school during the time; it was a time for the harvesting of the crops, so that the kids could go to the fields and work but my parents never did allow us to go to the field and work except on Saturdays and on Holiday. That is something that I always look forward to doing because I always wanted to work. Even in the summertime, kids would leave school early, get on the back of trucks and travel from Belle Glade, all the way up to Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, New York, New Jersey on the back of trucks to work. I mean, this is how they lived.” ( Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

“Everything in this area, the farmers and the school board worked together because the school district allowed us to be out of school during the time; it was a time for the harvesting of the crops, so that the kids could go to the fields and work but my parents never did allow us to go to the field and work except on Saturdays and on Holiday. That is something that I always look forward to doing because I always wanted to work. Even in the summertime, kids would leave school early, get on the back of trucks and travel from Belle Glade, all the way up to Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, New York, New Jersey on the back of trucks to work. I mean, this is how they lived.” ( Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

“Everything in this area, the farmers and the school board worked together because the school district allowed us to be out of school during the time; it was a time for the harvesting of the crops, so that the kids could go to the fields and work but my parents never did allow us to go to the field and work except on Saturdays and on Holiday. That is something that I always look forward to doing because I always wanted to work. Even in the summertime, kids would leave school early, get on the back of trucks and travel from Belle Glade, all the way up to Georgia, North Carolina, South Carolina, New York, New Jersey on the back of trucks to work. I mean, this is how they lived.” ( Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade)

In 1942, the Palm Beach School District allowed the closure of “negro schools” during harvesting months so that children could be available to assist with crop emergencies. That year, public schools closed on December 23rd to January 4th; however, black schools in Belle Glade started their school break period on November 6th to allow children to work the winter harvest. Black educators protested the school board on this decision. In 1944, the school board changed the school term to a consecutive nine month term, from September to early June.

Desegregation of Schools

B rown v. Board of Education produced the first court ruling against racial segregation in the education system. Oliver Brown, a parent, previously tried to file a case against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas for denying his daughter admission to a public school in 1951 but the district ruled in favor of the school board. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) then brought five separate lawsuits before the Supreme Court, including Oliver Brown’s case and let him take the position of lead plaintiff. In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional since it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. A year later, Brown v. Board of Education II gave local school boards and lower courts the responsibility to implement the original ruling. However, there was still resistance to implement integration. By 1964, more than 98% of black students in the South still attended segregated schools.

rown v. Board of Education produced the first court ruling against racial segregation in the education system. Oliver Brown, a parent, previously tried to file a case against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas for denying his daughter admission to a public school in 1951 but the district ruled in favor of the school board. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP) then brought five separate lawsuits before the Supreme Court, including Oliver Brown’s case and let him take the position of lead plaintiff. In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional since it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. A year later, Brown v. Board of Education II gave local school boards and lower courts the responsibility to implement the original ruling. However, there was still resistance to implement integration. By 1964, more than 98% of black students in the South still attended segregated schools.

Desegregation of Schools

Brown v. Board of Education produced the first court ruling against racial segregation in the education system. Oliver Brown, a parent, previously tried to file a case against the Board of Education of Topeka, Kansas for denying his daughter admission to a public school in 1951 but the district ruled in favor of the school board. The National Association for the Advancement of Colored Peo-ple (NAACP) then brought five separate lawsuits before the Supreme Court, including Oliver Brown’s case and let him take the position of lead plaintiff. In 1954, the Supreme Court unanimously ruled that racial segregation in public schools was unconstitutional since it violated the Equal Protection Clause of the 14th Amendment. A year later, Brown v. Board of Education II gave local school boards and lower courts the responsibility to implement the original ruling. However, there was still resistance to implement integration. By 1964, more than 98% of black students in the South still attended segregated schools.

“I remember [desegregation] because I was a teacher at that time and I was sent…to a white school as the assistant principal at that time. They sent one person in administration and they sent about two or three teachers…into those schools.” (Elizabeth Munnings, West Palm Beach)

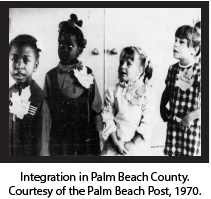

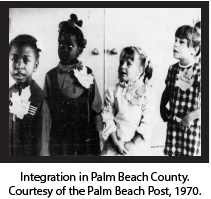

Integration of Schools

In 1956, after the Brown v. Board of Education ruling, lawyer William Holland Sr. tried to enroll his son at Northboro Elementary School, an all-white school in Palm Beach County. After his son was denied admission, Holland filed a federal lawsuit and lost. He kept persisting for several years in court. As a result, Palm Beach County began implementing integration, sending four black students to white schools in 1961. By 1965, that number increased to 65 students and by 1970 only one school remained 90% black. The U.S. District Court’s final ruling on the case declared Palm Beach County schools officially integrated in 1973. William Holland’s lawsuit forced integration and Robert Fulton, the superintendent, imple-mented these court orders.

“In 1964-68, Robert Fulton and William Holland fought for integration for all students in Palm Beach County, blacks as well as whites and others to have equal opportunity to achieve academic education. In 1961, integration was passed and today we have the Fulton Holland School District building on Forest Hill Boulevard in West Palm Beach, Florida in the memory of their outstanding accomplishments.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

“In 1964-68, Robert Fulton and William Holland fought for integration for all students in Palm Beach County, blacks as well as whites and others to have equal opportunity to achieve academic education. In 1961, integration was passed and today we have the Fulton Holland School District building on Forest Hill Boulevard in West Palm Beach, Florida in the memory of their outstanding accomplishments.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

The elders describe integration as something that had to happen, but it was not always easy.

“In 1964-68, Robert Fulton and William Holland fought for integration for all students in Palm Beach County, blacks as well as whites and others to have equal opportunity to achieve academic education. In 1961, integration was passed and today we have the Fulton Holland School District building on Forest Hill Boulevard in West Palm Beach, Florida in the memory of their outstanding accomplishments.” (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

The elders describe integration as something that had to happen, but it was not always easy.

“Now my brother…he was in the last class that graduated from Carver High School, which was 1970. His class was the last class to graduate from Carver High School…When that happened, they had a lot of race riots and stuff. You know, ‘cause the white kids did not want the black kids to come to school. They would fight them that would throw rocks and bricks.” (Gloria Chaney, Delray Beach)

“We knew all the teachers and then having to deal with different teachers, you know, of a different culture, a different race; it was a little difficult but it was kinda…like I said scary, intense. We didn’t know what to do and we were really afraid. (Allie Biggs, Pahokee)

Overcoming

Despite living through a society of discrimination, segregation and injustices, the elders, along with their communities, achieved, suc-ceeded, and overcame obst-acles. The elders took pride in their neighborhood and strived in academic achievement triump-hantly, despite racism in the educational system. Their narr-atives are a testament to their resilience, power, and for generations to generations.

“I had some good teachers and some good community people that kept me encouraged. That’s why I think it’s good for us, each one to reach one and try to encourage somebody.” – Allie Biggs, Pahokee

“I never wanted to give up. I taught my children that they were just as good as anybody that’s born. You either just as good as them or better than them; it was because of the way you carried yourself.” – Alfred Straghn, Delray Beach

“We had very dedicated teachers at our schools and they were determined to make sure that we would be qualified and able to finish high school and go on to college and pursue the kinds of education that we needed, and because we did not have a new textbooks because we did not have equipped science labs to work in, to do experiments, they improvised and brought things in and bought stuff for us to teach us…how to survive, actually and it certainly did.” – Myrtle Rains, Belle Glade

CREDIT LIST

Special thanks to the elders who participated and shared their lives with this project, our youth researchers who embraced this project fully and made it into something special. our interns who made the project move forward successfully, and the Children Services Council of Palm Beach County who made this project possible.

Sponsor

Children Services Council of Palm Beach County

Project Director

Dr. Alisha R. Winn

Researchers

Jovonna Morton, Suncoast Community High School

Cordayja Searcy, Atlantic Community High School

Zanae Talbert, Palm Beach Lakes Community High School

Essence Foster, Pahokee Community High School

Jermaine Mays, Glades Central Community High School

Interns

Josmery Botello, Palm Beach Atlantic University

Nicole DeAvila, Palm Beach Atlantic University

Catalina Rios, Palm Beach Atlantic University

Community Elders

Alfred “Zack” Straghn – Delray Beach, FL

Myrtle Rains – Belle Glade, FL

Allie Biggs – Pahokee, FL

Patricia Luma – Belle Glade, FL

Gloria Chaney – Delray Beach, FL

Lucille Fletcher – Belle Glade, FL

Mary Lopez – Riviera Beach, FL

Elizabeth Munnings – West Palm Beach, FL

Community Partners

Salvation Army Norwest Community Center – West Palm Beach, FL

West Palm Beach Police Athletic League – West Palm Beach, FL

The Student ACES Center – Belle Glade, FL

The EJS Project – Delray Beach, FL

Dr. Debra Robinson

The Palm Beach County School District

The Spady Cultural Heritage Museum

Stellar Marketing and Business Solutions

Consider the Culture

Bridgette Crowder – Transcriber

Photos and Articles Courtesy of

The elders and their famillies

The Library of Congress

Florida Memory Program

Palm Beach County History Online

Historical Society of Palm Beach County

National Education Association

The Palm Beach Post

The Miami Herald

South Florida Sun Sentinel

The New York Times

Content research, compilation, and editing by Catalina Rios and Dr. Alisha R. Winn, Consider the Culture. August 2021

Background References

Barszewski, L. (1996, November 1). Schools headquarters’ new name may honor integration struggle. South Florida Sun-Sentinel. https://www.sun-sentinel.com/news/-fl-xpm-1996-11-01-9610310533-story.html.

The Brown Foundation. (n.d.). Brown Case – Brown v. Board. https://brownvboard.org/-content/brown-case-brown-v-board.

Cornell Law School. (n.d.). 42 U.S. Code § 3616a – Fair housing initiatives program. Legal Information Institute. https://www.law.cornell.edu/uscode/text/42/3616a.

Ferris State University. (n.d.). Examples of Jim Crow Laws – Oct. 1960 – Civil Rights. Jim Crow Museum of Racist Memorabilia. https://www.ferris.edu/HTMLS/news/jimcrow/links/misclink/examples.htm.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County. (2020). Holland’s Fight for Equality. Facebook. https://www.facebook.com/HSPBC/videos/274774733935023/.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County. (n.d.). Cultural Heritage-African American History Month. Palm Beach County History Online. http://www.pbchistoryonline.org/page/cultural-heritage-african-american-history-month.

Historical Society of Palm Beach County. (n.d.). School Desegregation. Palm Beach County History Online. http://www.pbchistoryonline.org/page/school-desegregation.

History.com Editors. (2009, October 29). Plessy v. Ferguson. History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/black-history/plessy-v-ferguson.

History.com Editors. (2018, February 28). Jim Crow Laws. History.com. https://www.history.com/topics/early-20th-century-us/jim-crow-laws.

Jargowsky, P. A., Ding, L., & Fletcher, N. (2019). The Fair Housing Act at 50: Successes, Failures, and Future Directions. Housing Policy Debate, 29(5), 694–703. https://-doi.org/10.1080/10511482.2019.1639406

Pruitt, S. (2018, May 16). Brown v. Board of Education: The First Step in the Desegregation of America’s Schools. History.com. https://www.history.com/news/brown-v-board-of-education-the-first-step-in-the-desegregation-of-americas-schools

The Reconstruction Amendments. National Constitution Center. (n.d.). https://constitutioncenter.org/learn/educational-resources/historical-documents/the-reconstruction-amendments.

Times-Union Printing and Publishing House. (1886). Constitution of the State of Florida: adopted by the Convention of 1885, and ratified by the people at the election of November 2d, 1886.